How Much Fat Render When Cooking Steak Carnivore Diet

Cooking changes meat from its raw state into a finished masterpiece worthy of being at the center of a meal. But how and why does the application of heat cause changes in meat? To answer this question you need to know exactly what muscle fibers are, and what's going on inside them at specific temperatures. Understanding how protein fibers change during cooking will improve the quality of meat you cook!

How Temperature Affects Meat

Determining the doneness temperature of meat is important for two main reasons:

- Food Safety It's important that all possible foodborne pathogens are denatured before any meat is served. Professional cooks at restaurants know this fact well. Government regulations for sanitation and food safe doneness temperatures are in place to ensure public safety. For both USDA recommended doneness temperatures for food safety and chef recommended doneness temperatures, see the Chef Recommended Temperature Chart in our Learning Center.

- Food Quality Eating quality of food is a subjective evaluation of texture, flavor, and general mouthfeel (sensation in the mouth determined by such factors as moisture, richness, astringency, and temperature).

What are Muscles Made Of?

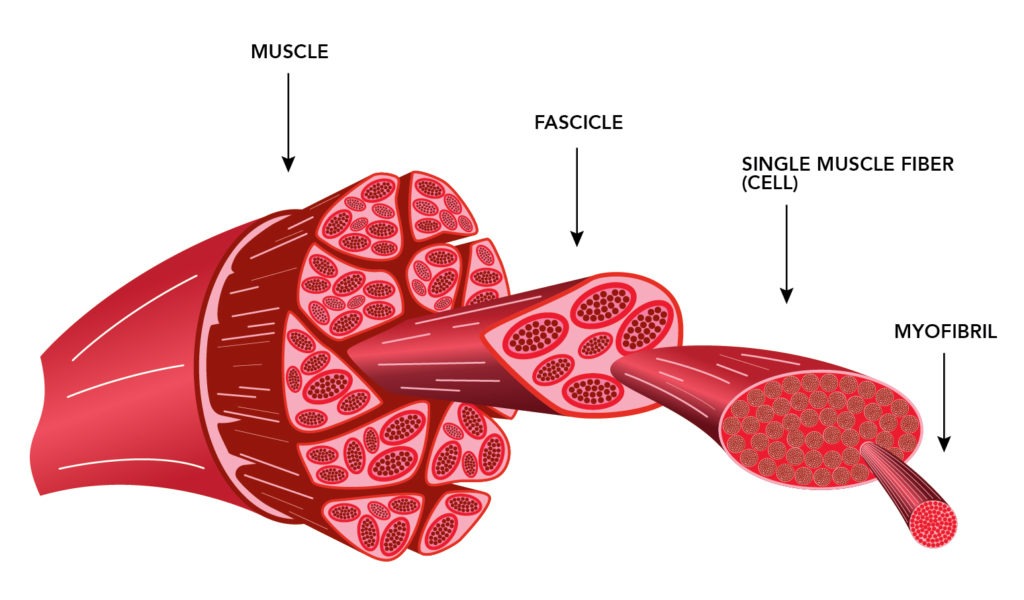

We often hear talk of muscle fibers and the "grain" of meat. Muscle fibers are long protein fiber strands and the direction of their formation is the grain of the meat (pictured right). Muscle meat of land animals is made up of many bundles of protein fibers. These bundles of protein fibers are called fascicles. Each muscle fiber is a multinucleated cell is made up of bundles of myofibrils. Each myofibril is made up of thousands of sarcomeres (contractile units) that are composed of myofilaments. And it's inside these sarcomeres where all the activity of contraction takes place in muscles. This is the general muscle structure found in beef, pork, lamb, and poultry.

We often hear talk of muscle fibers and the "grain" of meat. Muscle fibers are long protein fiber strands and the direction of their formation is the grain of the meat (pictured right). Muscle meat of land animals is made up of many bundles of protein fibers. These bundles of protein fibers are called fascicles. Each muscle fiber is a multinucleated cell is made up of bundles of myofibrils. Each myofibril is made up of thousands of sarcomeres (contractile units) that are composed of myofilaments. And it's inside these sarcomeres where all the activity of contraction takes place in muscles. This is the general muscle structure found in beef, pork, lamb, and poultry.

Why We Cook Meat

We are more highly evolved than our primitive ancestors who hunted and ate raw meat for survival. We eat for nutrition and pleasure. Cooking meat causes chemical changes that make it easier to chew and transform it into a mouthwatering culinary experience.

Specific chemical reactions occur in meat at distinct temperatures regardless of the cooking method used. Knowing what those temperature landmarks are and using precision temperature tools to determine doneness are they keys to becoming a meat cooking master! Some of the changes we can easily see when cooking meat are in:

- Opacity—The once translucent meat becomes opaque.

- Firmness—Meat can be tender or tough.

- Shrinking—Cuts of meat shrink in size as they approach doneness.

- Browning—The meat changes color from pink to gray/brown. Seared meat develops a deeply-colored crust.

- Moisture Loss—Liquid is expelled as the meat becomes more firm.

- Fat Breakdown—Intramuscular fat dissolves in the temperature range of 125-130°F (52-54°C), giving meat a succulent mouthfeel.

Color Changes

Myoglobin in meat is what gives it its pink/red hue. Myoglobin denaturation is responsible for the color change between raw and cooked meat. This change occurs at 140°F (60°C).

Opacity

When protein molecules denature, their coiled structure unfolds. These unfolded molecules then bump into each other and reconnect in a different configuration (coagulate), making it nearly impossible for light to pass through. This is what turns meat from translucent to opaque.

Moisture Loss

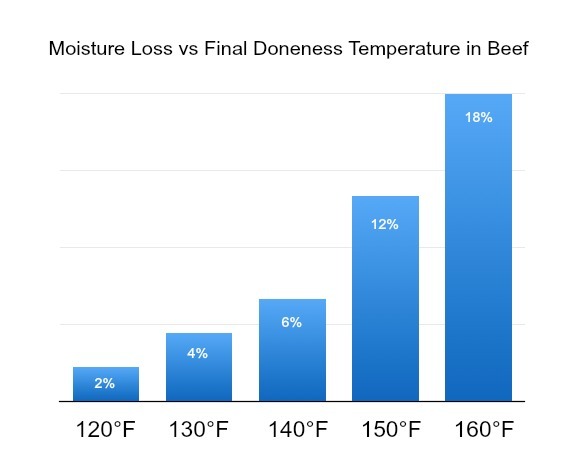

Juiciness is a considerable factor in determining the final eating quality of cooked meat. No matter how long it's brined, marinated, or even if it's cooked in liquid, moisture loss in meat is directly related to its final doneness temperature. Kenji Lopez-Alt has conducted his own research and found that the amount of moisture lost in meat increases dramatically once its internal temperature reaches 150°F (66°C). See the findings of Kenji's research in the chart below (from The Food Lab, by J. Kenji Lopez-Alt):

The effects of shrinking and firmness are what drive moisture loss in meat, and are directly related to subcellular changes that occur in the protein fibers during cooking. What happens that causes such a striking change?

Myosin and Actin in Muscles

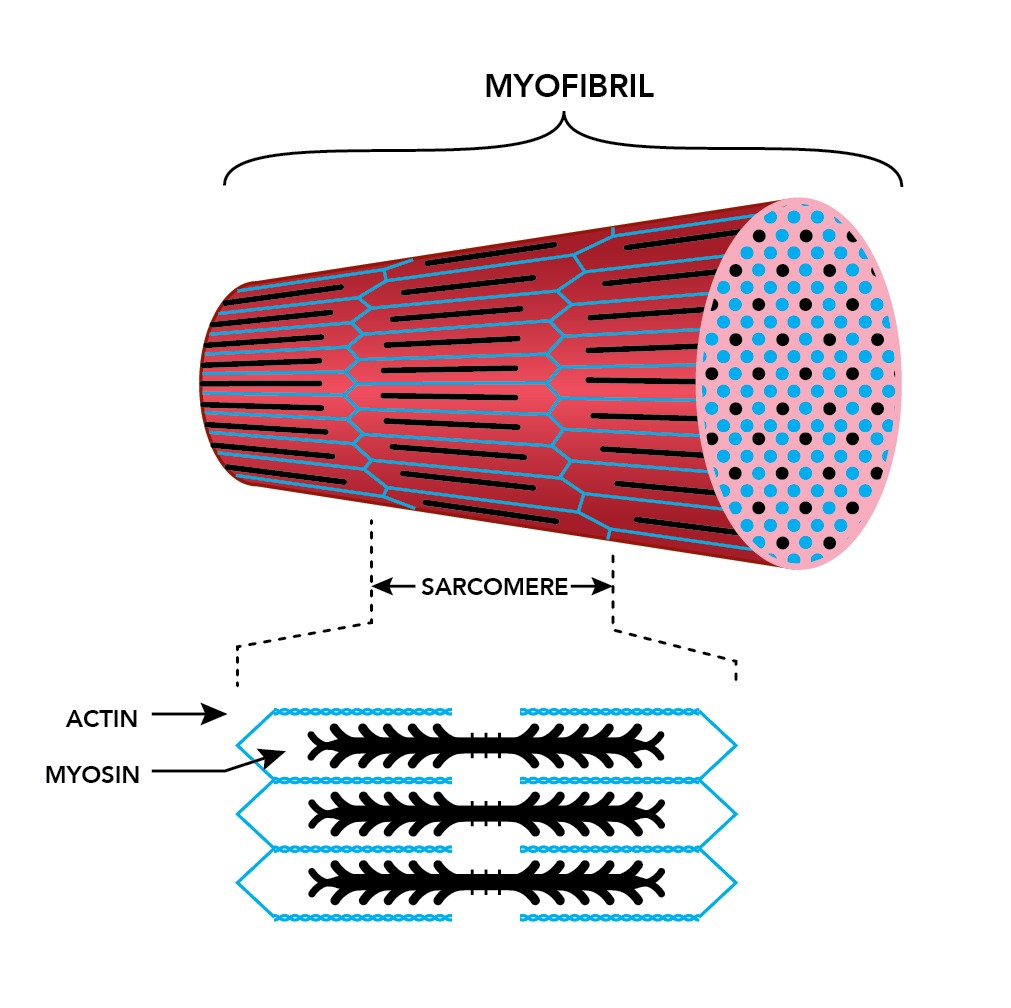

Of all the proteins in meat, myosin and actin are the most important from a cooking perspective. They are the myofibrillar proteins within each sarcomere that affect meat's texture and moisture-holding capacity. Let's take a look at how they work together in living muscles:

How Muscle Contraction Works

In the muscles of living animals, the action of the thick filament (myosin) heads attaching and pulling the thin filament (actin) is what causes muscle contraction. The contractile cycle of myosin and actin sliding is what causes skeletal muscle movement.

After slaughter, lack of blood flow to muscle tissue makes it impossible for the contractile cycle to complete its relaxation phase. The actin and myosin irreversibly combine in maximum muscle contraction, or rigor mortis. After rigor mortis, protease-based enzymes (calpain and cathepsin) are fully activated, degrading the meat. This degradation of the myofibrillar network of actomyosin is what tenderizes meat during the aging process.

Denaturation of Myosin and Actin

➤ Myosin: 104-122°F

Actin and myosin play a major role in the changes that take place in meat as it cooks. Myosin begins to denature around 104°F (40°C) with a striking change occurring at 122°F (50°C). Myosin is the thick filament responsible for actively shortening the sarcomere length as it pulls the actin filaments closer together. When myosin denatures it shrinks the sarcomere in diameter. This denaturation changes meat's texture from raw to being pleasantly cooked and still tender.

➤ Actin: 150-163°F

Actin denatures in a higher temperature range, and this reaction is what is primarily responsible for the toughening of meat fibers and moisture loss in cooked meat. It denatures in the range of 150-163°F (66-73°C). At this point the protein fibers become very firm, shorten in length, and the amount of liquid expelled increases dramatically. Your meat becomes tough and dry when cooked to these higher temperatures. This data accurately supports Kenji's research on the amount of moisture loss in cooked beef. At 150°F (66°C) the moisture loss doubles from where it is at 120°F (49°C).

Food scientists have determined through empirical research ("total chewing work" and "total texture preference" being my favorite terms) that the optimal texture of cooked meats occurs when they are cooked to 140-153°F/60-67°F, the range in which myosin and collagen will have denatured but actin will remain in its native form. —Cooking for Geeks, Jeff Potter

See the Difference!

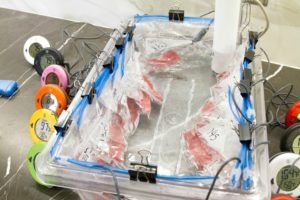

In the image below you can physically see how meat changes as the temperature rises. The meat changes in color, texture, visibly shrinks, and loses moisture. Using New York steaks, we cut them into equally-sized pieces and cooked them to the precise temperatures shown using a sous vide water bath. Changes in meat fiber diameter are visible as early as 115-120°F (46-49°C).

In the image below you can physically see how meat changes as the temperature rises. The meat changes in color, texture, visibly shrinks, and loses moisture. Using New York steaks, we cut them into equally-sized pieces and cooked them to the precise temperatures shown using a sous vide water bath. Changes in meat fiber diameter are visible as early as 115-120°F (46-49°C).

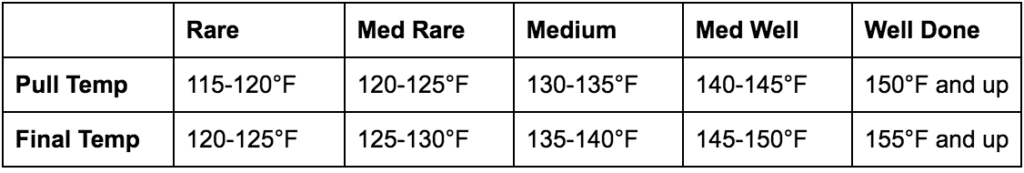

Now understanding what happens to your meat as it cooks, look at the chart of meat doneness temperatures below and see where your personal taste lies. Chances are, you like your steak cooked to a temperature that has allowed the myosin to denature, fats to render, but before the actin begins to denature.

Denatured myosin = yummy; denatured actin = yucky. Dry, overcooked meats aren't tough because of lack of water inside the meat; they're tough because on a microscopic level, the actin proteins have denatured and squeezed out liquid in the muscle fibers. —Cooking for Geeks, Jeff Potter

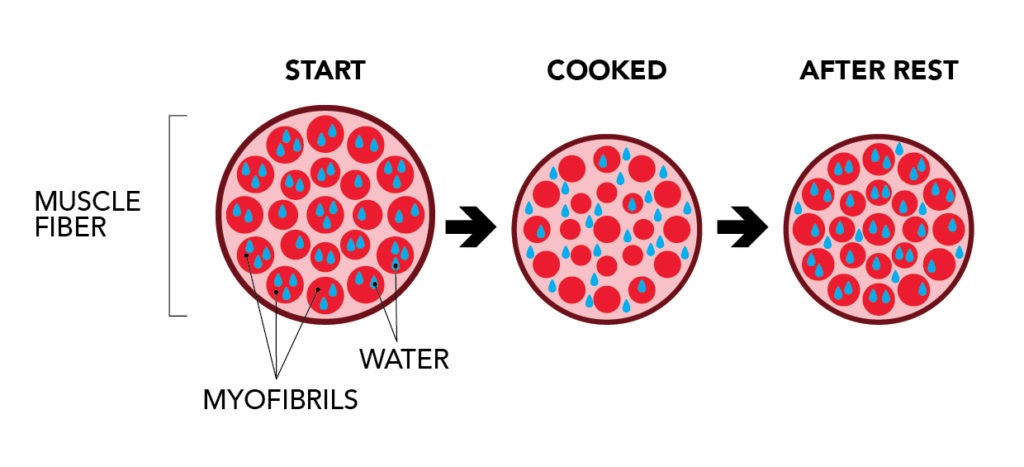

Resting Meat to Partially Reverse Moisture Loss

Protein denaturation that is responsible for causing meat to become firm and dry is partially reversible. Denatured actin cannot be changed, but myosin filaments can relax somewhat. This is evident when meat rests. The coagulated protein is able to reabsorb some of the lost moisture.

This knowledge really is the secret to preparing perfectly cooked meat every single time. Being able to track internal temperatures with precision let you know exactly what's happening inside your meat as it cooks. Overcooking meat by just a few degrees can truly mean the difference between a juicy steak and one that has become irreversibly tough. Cook with confidence!

Resources:

The Food Lab, Kenji Lopez-Alt

Cooking For Geeks, Jeff Potter

Cook's Science, Cook's Illustrated

On Food and Cooking, Harold McGee

Cooking-Induced Protein Modifications in Meat, Tzer-Yang Yyu, James D. Morton, Stefan Clerens, and Jolon M. Dyer, Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety | November 2016

How Much Fat Render When Cooking Steak Carnivore Diet

Source: https://blog.thermoworks.com/beef/coming-heat-effects-muscle-fibers-meat/